-

Moving Paint: The Art Of Earl Biss

Inside the Atelier Curation -

Atelier by relevant galleries

Our newly established exhibition space in Denver, designed for rare & rotating collections.

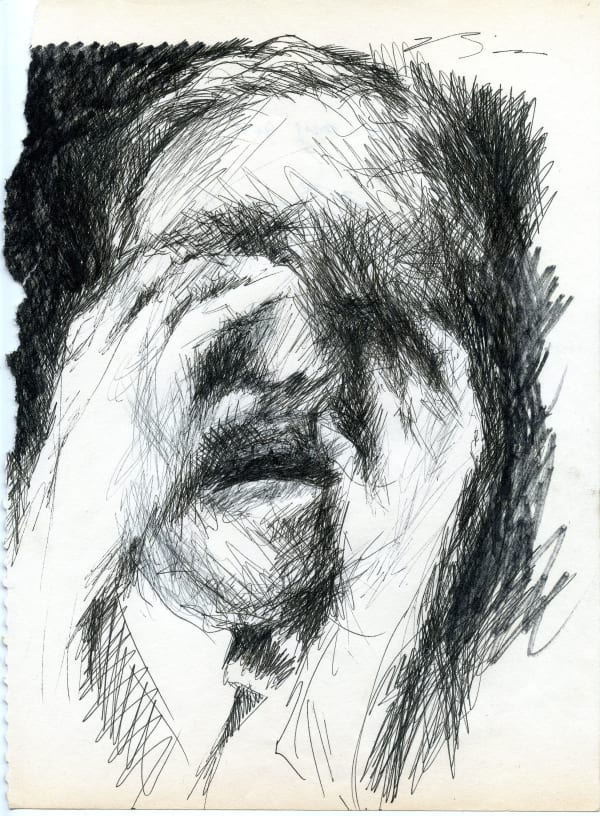

Housed in Atelier—our most experimental gallery concept—this exhibition captures the dynamic tension of Biss’s practice. Just as Atelier celebrates art in real time, Biss painted in the moment: blacking out his workspace, surrounding himself with 60 blank canvases, and entering what friends described as “the zone,” sometimes painting nude, often painting in trance. In keeping with Atelier’s mission to showcase “art in motion,” this presentation explores not just the finished works, but the mythology, ritual, and endurance behind them. This is not merely an exhibition—it is a glimpse into the fire of creation. -

-

Atelier's Current Curation

-

Untitled Aspen Trees & The Rockies

Untitled Aspen Trees & The Rockies -

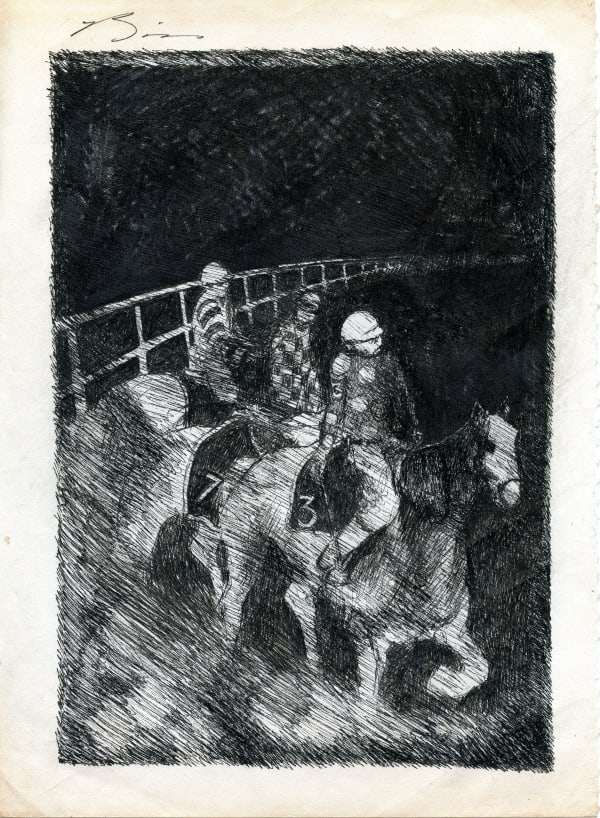

Watching the Camp 1987

Watching the Camp 1987 -

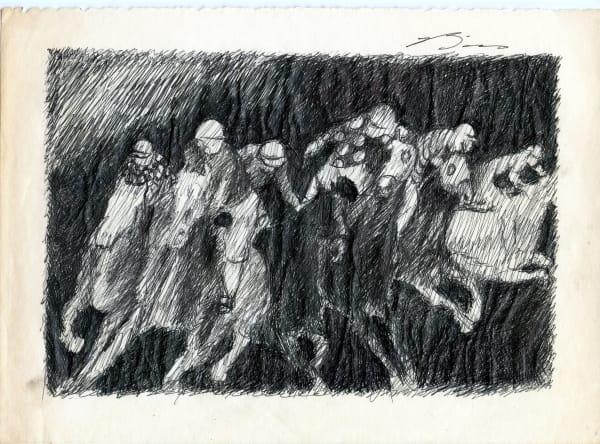

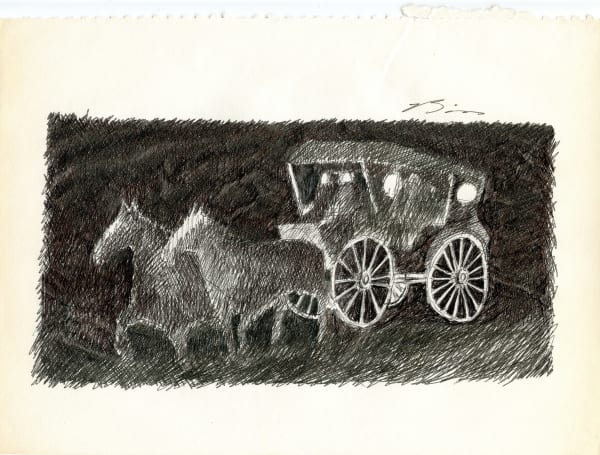

Passing Windy Point 1979

Passing Windy Point 1979 -

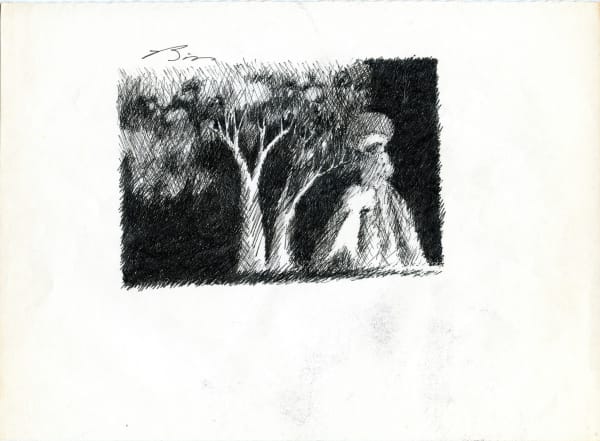

Strolling Through a Poplar Grove at the Base of Black Canyon 1997

Strolling Through a Poplar Grove at the Base of Black Canyon 1997

-

A Bright Afternoon in France

A Bright Afternoon in France -

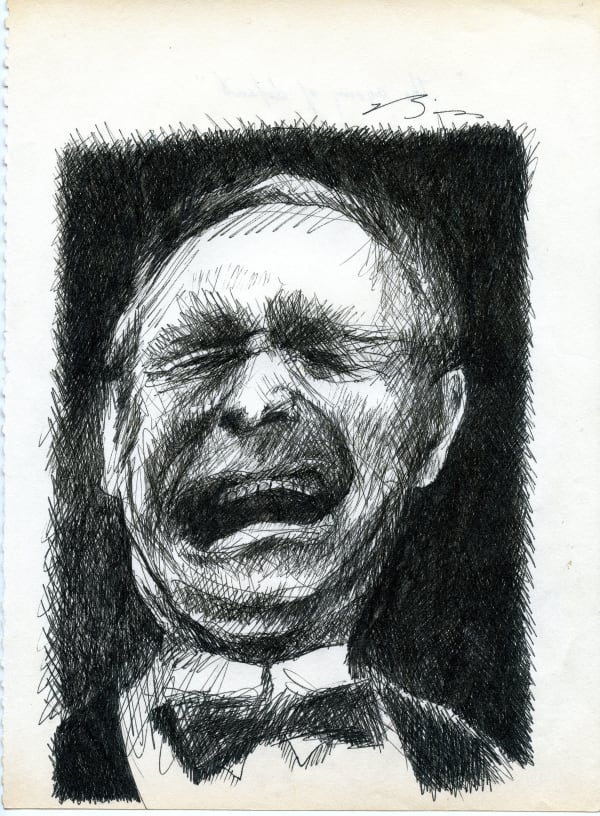

A Painting for Edvard Munch 1980

A Painting for Edvard Munch 1980 -

Earl Biss, Early Morning Camp

Earl Biss, Early Morning Camp -

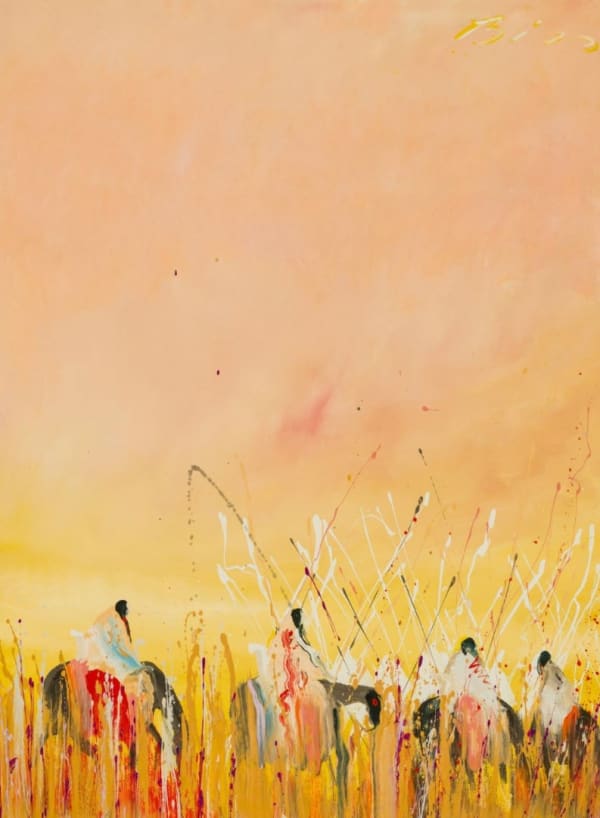

Five Warriors in Orange 1981

Five Warriors in Orange 1981

-

-

-

-

-

The Quality of Paint

"When I was first starting, or when I realized that there was a chance I might be recognized in the art world, I fought rigorously to let people know that I was an artist first, not just an Indian artist. I feel this was because of my awareness of the fine arts, my European influences, and my knowledge that fine art, especially oil painting, has its roots in Europe.Success by being Indian is very dangerous, as it tends to suggest regionalism, or something that could be too easily typed as a fad, or something that is in style. And something that is in style goes out of style so easily, discarded by the public. I know my artwork is much more important than that. There are too many artists, in my opinion, who are riding on nationality, where they come from, whether it be a Black artist, a cowboy artist, an Indian artist, or whatever. There are isms. Indianism is, in a way, phony and very shallow in the world sense. If a person has something to say, it shouldn’t be just to the white man, it shouldn’t be just to the negro, it shouldn’t be of just political ilk.

I believe that important artists should speak to humanity as a whole. Knowing this at an early age, I fought against being recognized as an Indian artist. However, in the early 70s, Navajo jewelry was very popular at the time. I happened to be a jeweler. Not many people realize this, but I made my entire living from turquoise and silver jewelry before my oil painting started selling. I took advantage of this. Yes, I did.

But I love my artwork, which comes from such deep feelings; I wanted to keep it pure. So for years, I painted totally abstract. But I found in this Indianism a very handy vehicle to obtain focus for my oil paintings. I found that many people who collect oil paintings are very sophisticated, intellectual, and well-read in art history. And they would recognize the difference between a phony and a real painter.

I became comfortable with this. And I think that as part of the maturing process, I realized I am an Indian. I am very proud of being an Indian. I am an oil painter. And I am very proud of being an oil painter. It was a natural process that made me come to realize that I am many things at once. There is nothing wrong with being an Indian artist who is also a very fine oil painter. I am very proud of what I am, and I am not trying to fight something that I have no power over. This has really come about, I believe, in age.

I want to keep my statement pure, and in an effort to do that, I like my paintings to be appreciated for the quality of the paint, much more than the images that I portray, because that is what truly makes an oil painter. The quality of paint. The quality of paint. Yes. Yes."

"Moving Paint: The Art of Earl Biss": American Impressionist Painter (1947-1998)

Current viewing_room